Technology may be changing faster than laws can keep up, but that cannot be said of DNA and its use in paternity claims.

The recent decision of the Court of Appeal in the case of AK v HA-P [2020] JMCA Civ 25 has been heralded as a major breakthrough in the use of technology to determine paternity in court proceedings. From my perspective, the judgment really highlights the slow pace of legislative change in Jamaica and points to simple amendments that could have been made to the Status of Children Act many, many years before the child, in this case, was even conceived.

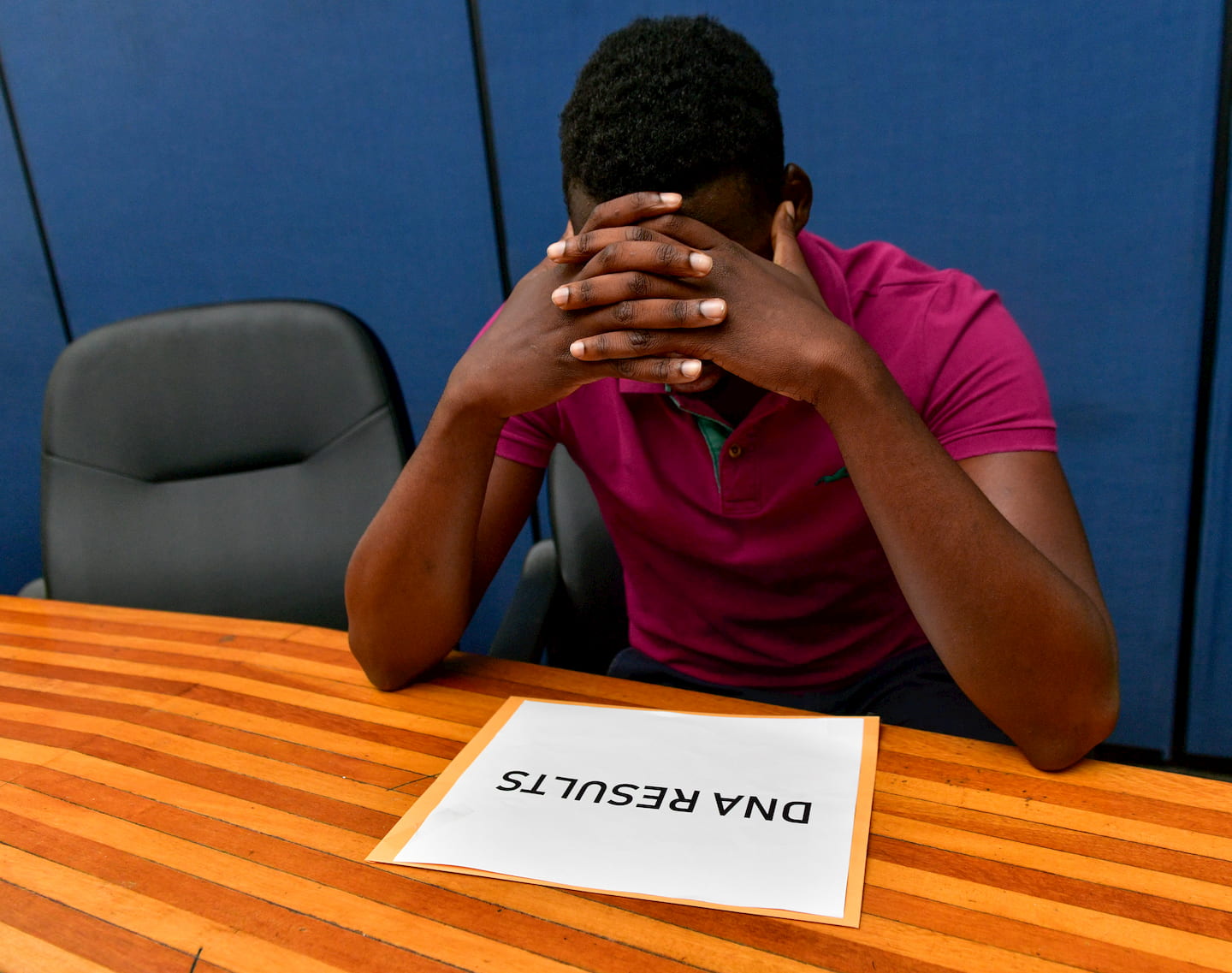

The background to the case is that the claimant commenced proceedings in Court to seek a declaration of paternity, as well as consequential orders concerning the child’s birth certificate, custody and access to him. With the child’s mother’s consent, the claimant had done a DNA test using saliva samples before filing his claim, and the results showed that there was a 99.9998% probability that he was the child’s father.

In order to determine the paternity claim, the court reviewed the Status of Children Act, which was enacted in 1976, and confirmed the following:

- The Act provides the only statutory framework for determining paternity.

- It only includes references to blood tests. No other scientific testing methods are mentioned in the Act.

- No party can be compelled to provide a blood sample so, if there is a refusal to cooperate, the court may only draw proper inferences from that fact.

The Court disposed of the issues raised on the appeal by finding that:

- Once a child is under 16 years old, the consent of the parent or guardian is required for a blood test to be taken, so a court’s order for blood samples to be taken to determine paternity must be contingent on the consent of the parent who has care and control of the child.

- Based on section 11(6) of the Act, the party who has applied for the blood tests to be done must pay those costs.

- Parliament has made no provision to include bodily samples, such as saliva, in order to determine whether a person is or is not excluded from being the father, so a court may not make an order for salvia samples to be taken to conduct a paternity test.

- In determining a paternity claim, a court may consider any relevant and admissible evidence in relation to the issue. For this reason, a test that was conducted by consent of the parties may be admitted in evidence, provided that it is “cogent, [satisfies] the requirements necessary to establish authenticity and . . . taken together with an assessment by the trial judge of all the other pieces of evidence.”

Ultimately, the Court of Appeal determined that the weight of the evidence of the DNA test result obtained from saliva samples would be an issue for the trial judge to determine, but that such evidence would not simply be excluded because it is not the result of a blood test, as contemplated by the Act.

The challenge I find is that a careful review of the Act several years ago when DNA tests became the default procedure for determining paternity might have obviated the necessity for the issues in this appeal to be considered at all. The Learned Judge in the Court of Appeal considered sections of the Law Reform Family Act in the UK, which was amended to allow for “scientific tests” to be used to determine paternity. The same is true in other jurisdictions, so Jamaica needs to catch up.

Sherry Ann McGregor is a partner, mediator and arbitrator in the firm of Nunes Scholefield DeLeon & Co. Please send questions and comments to lawsofeve@gmail.com.